Crisis Brews In Darjeeling’s Tea Gardens

In the last three years, 20 gardens have changed hands, and 90 per cent of the buyers are from non-tea background.

In 2015, Prime Minister Narendra D Modi presented Queen Elizabeth an award-winning variety from the Makaibari estate on his visit to the United Kingdom.

Last month, the ‘Champagne of teas’ made it to the G20 hamper for world leaders, along with Sunderban honey, Araku Valley coffee, and saffron from Kashmir — items representing the unique biodiversity of the country.

No doubt, Darjeeling tea sits snugly among products that represent the best India. But there is trouble brewing in the 87-odd gardens that produce the golden elixir. Myriad challenges, from lower production to muted demand, and falling prices to labour absenteeism are pushing the owners to sell out.

The Chamong Group, the largest producer of Darjeeling tea, accounting for about 16 per cent of the production, is the latest to put a clutch of its gardens on the block, according to market sources.

The group has 13 estates that produce 1.1 million kilograms (mkg). Ashok Lohia, chairman, Chamong Group, declined to comment.

Lohia is not the only one in the ‘Queen of Hills’ looking to cut his losses.

In the last one year, Jay Shree Tea AND Industries, led by Jayashree Mohta, elder daughter of the late B K Birla, has sold three estates.

“At least 60 per cent of Darjeeling estates are up for sale,” says Anshuman Kanoria, chairman, Indian Tea Exporters Association (ITEA), adding there were few buyers and hardly any from the tea industry.

Kanoria has two gardens — Tindharia and Goomtee — and is looking to sell the former.

The storied Goodricke Group is not looking to sell gardens “at the moment”. “But, going forward, we don’t know what is going to happen,” says Atul Asthana, managing director and CEO, Goodricke.

In the last three years, 20 gardens have changed hands, and 90 per cent of the buyers are from non-tea background, says Kanoria.

Flush of trouble

The year has been particularly agonising for the industry.

About 50 per cent of Darjeeling tea is exported and key export destinations, such as the European Union, have taken a knock. In the domestic market, producers have little bargaining power.

Jay Shree Tea once accounted for about 10 per cent of Darjeeling tea production. But in the last five to six years, it has sold gardens and halved its output.

Costs were high, yields low, and vagaries of weather play havoc with production, points out Jayashree Mohta, chairperson and managing director, Jay Shree Tea .

Jay Shree still has three estates in Darjeeling and the intent is to hold on to them.

“We have a huge client base across the globe — mainly Germany, France, UK, USA, and Japan. The likes of Harrods and Fortnum & Mason keep our teas,” says Vikash Kandoi, executive director and Mohta’s son-in-law. “But if it is unviable, how long can you continue?”

It is a question most owners are left asking themselves.

The average price for Darjeeling leaf at the Kolkata auction from January to September was Rs 353.82 per kg, compared to Rs 351.12 per kg in 2022. That is the average.

On many occasions, prices have been significantly lower than last year while wages, which account for 60 per cent of production cost, are on the rise.

The crop in the peak period of first and second flush — the prized produce of Darjeeling accounting for the bulk of its revenues — has been lower than last year.

“Gardens are going to incur huge losses this year,” Goodricke’s Asthana notes.

What makes things particularly difficult is that the cost of production in Darjeeling is high — Rs 800 to Rs 900 a kg for the gardens on a higher elevation. So, the more you produce, the more you lose.

Still, the pain points for Darjeeling are not the premium first and second flush, but the balance that accounts for 60 to 70 per cent of the volume.

The price realisation for the prized production does not quite compensate for the loss in the volume segment.

“The problem is, we don’t see any light at the end of the tunnel. We don’t understand where new demand is going to come from,” Kanoria says.

At least three gardens are known to have shut down in recent weeks, though the total number of closures is said to be higher.

Lost sheen

The uncertainty in Darjeeling is not a recent phenomenon.

The Gorkhaland agitation in 2017 brought the industry to its knees.

Many overseas buyers switched to Nepal teas, a poor cousin of Darjeeling, but with similar properties.

Although Darjeeling tea was among the first Indian products to get the GI (geographical indication) tag, recall and awareness have been low.

In the domestic market, too, the cheaper Nepal teas have made inroads.

Imports from Nepal rose from 9.21 mkg in 2021 to 17.36 mkg in 2022.

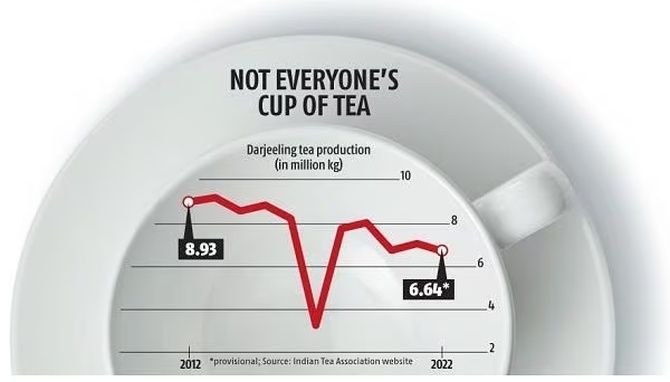

Climate change is playing its part. Production used to be 10 to 12 mkg a year, and even higher in some years. But it has been consistently below the 10-mkg mark since 2009.

Even for the small produce — about half a per cent of total tea production — there is not enough demand.

There was a sheen about Darjeeling tea, but not any longer.

“The younger generation is not discerning,” says Mohta.

Kandoi points out that the world is drinking Darjeeling tea, but India is not.

“We have to do some sort of promotion. The government has to help us with that,” he adds.

Touch of hospitality

In 2019, the West Bengal government allowed tea gardens to use 15 per cent of their total grant area, up to a maximum of 150 acres, for tea tourism and allied business activities.

In 2020, Taj checked into Darjeeling with Chia Kutir, set in the famous Makaibari tea estate owned by Luxmi Tea.

The project, in partnership with the Ambuja Neotia Group — lease holder of the part that houses Chia Kutir — is a runaway success.

Tea garden owners and hospitality majors have tried to make good of its ripple effects, but not all are working.

Some producers believe it can be an additional revenue stream but cannot compensate for a tea estate’s losses. And it requires deep pockets.

Darjeeling tea has had quite a following — from the British royalty to Satyajit Ray’s fictional private investigator, Feluda.

Given the magnitude of the challenge, no less than Feluda’s famed magajastra, or ‘brain power’, can crack the puzzle.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article